Case Studies of Chronic Insomnia Patients Participating in Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia

Article information

Abstract

Background and Objective

Pharmacotherapy currently widely used in the treatment of insomnia can be helpful in transient insomnia, but research regarding its effectiveness and safety of long-term use is not enough. Therefore, to complement the limitations of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of patients with insomnia, non-pharmacologic treatment methods (cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT) are used. But CBT for insomnia appear to be costly and time-consuming compared to pharmacotherapy, clinical practice in the field can be difficult to be applied. We took the format of group therapy rather than individual therapy to complement the disadvantages of CBT and now we would like to have a thought into its meaning by reporting the effectiveness of group CBT for insomnia.

Methods

Patients were recruited at Sleep Center of St. Vincent’s Hospital, 2 men and 3 women led to a group of five patients. CBT is a treatment for correction factors that cause and maintain insomnia, it includes a variety of techniques such as sleep hygiene education, stimulus control, sleep restriction, relaxation and cognitive therapy. A series of treatment were performed five sessions once a week with a frequency from February to March 2012 and were proceeded for about 1 hour and 30 minutes per session.

Results

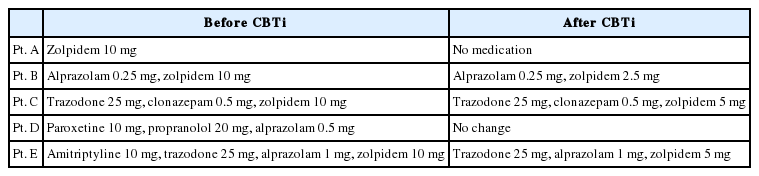

Results indicated that the subjective quality of sleep and sleep efficiency of all patients improved and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Beck Depression Inventory were decreased in spite of reducing dose of medication.

Conclusions

Like these cases, we can contribute to reduce the time and economic burden by performing group CBT for insomnia rather than individual therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is defined as a state in which an individual has difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, or experiencing unrefreshed sleep despite ample opportunity and situation to sleep.1 One third of the total population experiences at least intermittent insomnia, and approximately 10 to 15% experience chronic sleep problems. Nevertheless, general awareness and interest in insomnia are insufficient, and accurate diagnosis and adequate treatment of insomnia are often not addressed in clinical settings.2–5

Pharmacotherapy is currently widely used in the treatment of insomnia and can be helpful for transient insomnia, but research regarding its effectiveness and safety of long-term use is not sufficient. Therefore, to overcome the limitations of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of patients with insomnia, non-pharmacological treatment options (cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, CBTi) are used. CBT is a psychotherapeutic approach which addresses maladaptive cognitive processes and behaviors through goal directed, explicit systematic procedures. The main purpose of CBTi is to eliminate maintaining factors that are presumed to perpetuate chronic insomnia.6 There have been studies reporting that CBTi is effective in primary insomnia as well as in secondary insomnia associated with the use of drugs and substances, medical problems or psychiatric disorders.7 However, studies have shown that CBT appears to be costly and time-consuming compared to pharmacotherapy, and have addressed difficulties in implementing CBTi within clinical practice due to the lack of practitioners.8–16 The authors implemented group CBTi rather than individual therapy to enhance cost effectiveness. In this paper, we report several cases of patients who participated in group CBTi and were successful in reducing or discontinuing their sleep medication.

METHODS

Five patients (two men and three women, mean age = 55 ± 6.85) were recruited from the Sleep Center of St. Vincent’s Hospital. All patients reported sleep disturbance and voluntarily participated in group CBTi. This report refers to five patients who were randomly assigned as Patient A, B, C, D and E.

Patient A was a 54-year-old nun who described herself as ‘detail-oriented and perfectionistic.’ She was diagnosed with breast cancer 5 years ago when she visited the hospital for a routine examination. Along with breast cancer, she was also diagnosed with depressed mood and insomnia. When she visited about 6 months ago, her back pain became worse, which subsequently made it more difficult for her to sleep. She initiated treatment in pain control and physical therapy in the Department of Rehabilitation medicine as an outpatient. She was prescribed 10 mg of Zolpidem. Her pain and insomnia improved, but she continued to take sleep medication on an as needed basis. Her main goal for participating in this treatment was discontinuation of her sleep medication.

Patient B was a 52-year-old public official who had timid and sensitive personality. He started to experience anxiety and heart palpitations, physical symptoms of dizziness and sleep disorders about two years ago when his mother passed away. He reported taking sleep medication, and claimed he had no improvement. He reported participating in cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia previously, which he reported was not very effective.

Patient C was a 64-year-old woman who experienced anxiety symptoms. She reported visiting the hospital with main complaints of insomnia which started six years ago when her son got married with the start of frequent and repetitive conflicts with her daughter-in-law. Approximately 2 months ago, she returned to the hospital after arguing with her daughter-in-law, which in turn exacerbated her insomnia. Since then, she has made efforts to reconcile with her daughter-in-law and has also started taking sleep medication, which has somewhat improved her sleep.

Patient D was a 46-year-old construction company worker who became nervous and experienced worsening physical symptoms such as headaches under stress. His main sources of stress were conflicts with his wife and work. He was diagnosed with anxiety disorder at a private psychiatry clinic, and he had been consistently taking medication for 7 years prior to visiting the hospital. About 1.5 years ago, he was involved in an automobile accident, which amplified his anxiety and hyperarousal symptoms. He reported that since the accident, he has been experiencing symptoms consistent with posttraumatic stress disorder, including severe nightmares.

Patient E was a 59-year-old woman who first visited the hospital about two years ago after her brother-in-law failed to return money that she had lent him, leaving her with depression and insomnia. About one year ago, she began to care for her mother-in-law, who had dementia, and the additional stress exacerbated her insomnia. She reported suffering from insomnia almost every night despite taking sleep medication.

Based on Spielman and Glovinsky’s model (1991), CBTi is a treatment that targets perpetuating factors that cause and maintain insomnia, including a variety of techniques such as sleep hygiene education, stimulus control, sleep restriction, relaxation and cognitive therapy. Treatment sessions consisted of five weekly sessions between February and March 2012, and each session lasted for about 1hour and 30 minutes.

In the first session, members of the group introduced themselves and received sleep education and orientation about CBTi. All patients stayed long in bed at a wake state or napped too much to compensate for the lack of overnight sleep, which eventually leaded to the chronic insomnia, interventions to correct the inadequate sleep condition were performed. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were used to evaluate the state of sleep quality and patients’ mood in a subjective manner. In addition, in order to check the patients’ sleep patterns more specifically, the patients were asked to keep a weekly sleep diary. Sleep diaries were checked every session by reviewing the diaries to see changes in sleep patterns during the treatment period, and were also used to make recommendations to prescribe sleep and wake times.

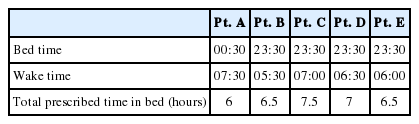

In the second session, we performed behavioral therapy, including sleep restriction and stimulus control to modify mal-adaptive sleep habits that served to maintain insomnia. For example, Patient A was told to correct the irregular bedtime schedule, and to try to correct maladaptive habits, such as watching TV lying on the bed before falling asleep. For patient B, his sleep diaries revealed that he had prolonged his sleep onset latency. He reported lying in bed for more than two hours due to sleep worry. Patient B was told not to stay in bed unless he was able to fall asleep within 30 minutes. During these sessions, we prescribed a time in bed which was tailored to each individual patient to increase sleep efficiency. Additionally, the patients fixed their wake time and considered their desired sleep hours based on their average number of hours of sleep. For example, patient A usually slept about 6.2 hours per night. She desired to wake up at 7:30 AM and sleep for 7 hours per night, so her bed time was set at 00:30 AM. She adhered strictly to her ‘time in bed’, and after a week, her sleep efficiency was increased from 72.7% to 84.7%. Prescription for sleep and wake times can be found in Table 1.

In the third session, all patients were introduced to and practiced progressive muscle relaxation to decrease the levels of hyperarousal. It is well-known that chronic insomnia patients experience heightened hyperarousal characterized by excessive worrying. Relaxation techniques can help decrease hyperarousal states and promote sleep.17 Patients were generally satisfied, and were instructed to practice relaxation techniques at home 2–3 times per day with other family members, who read the script for them, or through the CD that was distributed to them.

During the fourth session, cognitive restructuring was implemented to target maladaptive and dysfunctional beliefs about sleep. We checked the patients’ distorted cognitions about insomnia and replaced these automatic thoughts with rational and adaptive thoughts.18 For example, patient C thought that she always had to sleep for at least 8 hours. If she could not sleep for 8 hours, she interpreted it as abnormal and worried excessively. However, after receiving sleep education that taught her that sleep time differs depending on the individual and that other extraneous factors had little to do with sleep, she was able to realize that her belief about sleep was not reasonable and was able to let go of her strong belief that she needed 8 hours of sleep. In the last session, we summarized the course of treatment and discussed maintaining treatment effects and relapse prevention.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index is a self-rated questionnaire which assesses sleep quality and disturbances over a 1-month time interval. Nineteen individual items generate seven “component” scores; subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction.19

Beck Depression Inventory created by Dr. Aaron T. Beck is a 21-question multiple-choice self-report inventory, which is one of the most widely used instruments for measuring the severity of depression.20

Sleep diaries are a record of an individual’s sleeping and waking times with related information, usually over a period of several weeks. It is self-reported or can be reported by a care-giver. Information contained in a sleep diary includes the following; Bed time, wake time, lights out, sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, number of awakenings, sleep quality, the name, dosage and timing of sleep medications, and daytime functioning.21

Statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test.

RESULTS

Results showed that the subjective quality of sleep and sleep efficiency of all patients improved, and PSQI and BDI scores decreased, even after reducing the sleep medication dosage (Table 2 and 3). For example, patient A achieved a 53.3% reduction in her sleep latency although her total sleep time was almost the same after study completion. In addition, her nocturnal wake time after sleep-onset decreased 66.6% and sleep efficiency increased 16.3%. PSQI and BDI scores of patient A decreased after CBTi and showed statistical significance (Table 4).

Additionally, she was able to replace dysfunctional beliefs associated with sleep with more adaptive cognitions, and as a consequence, the level of cognitive arousal diminished throughout CBTi. All patients were able to realize to some degree that their dysfunctional beliefs about sleep were not reasonable, and changing these had a strong impact on improving insomnia symptoms.

DISCUSSION

There is ample evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) is effective for secondary or comorbid insomnia as well as primary insomnia. This was evident from the improvements seen in our study. However, there may be some problems regarding time and cost-effectiveness of CBTi. Thus, implementing a group format such as the one used in this current study can contribute to reducing the time and economic burden of CBTi compared to individual therapy.

Furthermore, patients receive empathy and support from other patients in the group who also have insomnia. However, there are individual differences in therapeutic effects despite all patients receiving the same treatment. This may partially be due to treatment adherence, as patient A who participated actively and completed daily sleep log and relaxation therapy was able to reach her treatment goals by achieving satisfying sleep without sleeping pills.

Numerous clinical trials have evaluated CBTi as an effective treatment modality and reported that the combination of CBTi and supervised tapering of sleep medication would enhance the outcome.22–25 In our study, insomnia patients receiving both supervised tapering and CBTi reported improved sleep quality and decreased sleep medication dosage. However, the current study did not include a control group, which limits our ability to make a strong conclusion.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.