Later Chronotype Correlates With Severe Depression in Indonesian College Students

Article information

Abstract

Background and Objective

The correlation between late chronotype and depression has been well documented, but reports from the equatorial area, where the sun shines throughout the year with less seasonal variation, are limited. In the present research study, we sought to 1) examine the relationship between the chronotype and mental health symptoms in an Indonesian student population and 2) explore the characteristics of those who lie at the extreme chronotype and psychometry.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study including undergraduate students in an Indonesian university (n = 493). We used the Munich Chronotype Questionnaires and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale to assess the chronotype and mental symptoms, respectively. Following this, a follow-up with an in-depth interview on the selected population at the extreme end of the chronotype was performed as an exploratory approach to identify their common characteristics.

Results

Among the tested parameters, the depression score was significantly associated with chronotype (p = 0.003), replicating previous findings from other areas with higher latitudes. The correlation persisted when males and females were analyzed separately (p = 0.008 and 0.037, respectively). A follow-up qualitative analysis revealed a potential subclinical, unrealized depression among the subjects; our findings revealed the use of smartphones during or before bedtime as a common factor among those with later chronotypes.

Conclusions

There is a correlation between depression score and chronotype among Indonesian college students, where subjects with later chronotype are more likely to have a higher depression score.

INTRODUCTION

Most, if not all of the living creatures on the earth perform their activities based on the day-night cycle: circa diem, which literally means ‘around one day’, and from which the term ‘circadian’ was derived [1,2]. In fact, –43% of protein-coding genes in mammals are expressed in a circadian manner [3]. Thus, the circadian rhythm is not merely a biological phenomenon interesting for scientific exploration, but might be playing more roles than previously thought. Unfortunately, in the modern society, where humans are becoming more independent of the sunlight and increasingly ignoring natural circadian cues, the circadian rhythm could be the Achilles’ heels that we are consistently attacking. The circadian rhythms are regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus upon the daylight illumination signal from the retina. The SCN controls the sleep-wake temporal cycle, as well as all the diurnal physiological functions, such as hormone secretion and autonomic functions [4]. Chronotype, which is the natural inclination of the body to sleep at a certain time, is closely related to circadian rhythm. There are different types of chronotypes that reflect varying individual intrinsic synchronization responses to stimulus changes over the day.

Since humans have evolved under a robust day-night cycle with the sunlight as the main cue, the introduction of artificial light emitted by electric illuminations may shift the internal clock, and in turn, induce changes in human physiology [5]. In particular, youths and students are at a greater risk of having a disrupted circadian rhythm, as reflected by their later chronotype, i.e. sleep later at night and wake up later in the morning [6]. It has been well established that later chronotype is associated with a range of psychopathologies, including depression, substance abuse, and suicidal behavior [7-9]. However, most of the chronotype studies have been conducted in high-latitude regions where the daylight length varies across seasons [10]. In tropical countries, where around 40% of the world population lives, the sun shines throughout the year, causing minimal effect on the seasonal chronotype adaptation. Thus, it is important to assess whether individuals who live in the equatorial area are similarly affected by the variation in chronotype, and display the same trend as the sub-tropical inhabitants as shown by a previous meta-analysis [10].

In the present study, we examined the psychometry and chronotype of the college students in Indonesia, a country that lies precisely on the equator. Our site of research is situated at 1.3020° North and 124.9134° East proximate to the equator, thus providing a subject group with very distinctive characteristics of tropical inhabitants. This research aimed to 1) assess the associations between chronotypes with depression, anxiety, and stress (DAS) among the students in an Indonesian university by applying Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS) and Munich Chronotype questionnaires (MCTQ) as quantitative measurements for mental health and chronotype, respectively [11,12], and 2) explore the characteristics of those who lie at the extreme ends of the chronotype and psychometry. For the first aim, we hypothesized that chronotype is associated with DAS in Indonesian college students, whereas for the second aim, the author did not behold any prior assumption due to its exploratory nature.

METHODS

Sample Selection

The study was performed at the Public Health Department of Manado State University, Indonesia, and included all the undergraduate students from year 1 to year 4 at the time of research. Permission to carry out survey was sought from the appropriate university authority (Surat Izin No. 031/6-IKM). Informed consent was obtained from the participants. To ensure reliable and generalizable results, a total sampling technique was applied by distributing the questionnaires to all the students after a class session, apart from those that were unwilling to participate; no credits nor punishment were given for agreeing or refusing to participate in the study. For the qualitative study, a group of students at the extreme end of late chronotype with high depression scores were interviewed.

Questionnaires

To assess the chronotypes, we employed an Indonesian version of the MCTQ translated and validated in our center. We choose the MCTQ because it was shown to be sensitive in detecting chronotype shifts between high and low latitudes [13]. The MCTQ included questions on participants’ sleep duration and pattern during weekdays and weekends, and reported the sleep-deprivation corrected mid-sleep time at free days (MSFsc) and average sleep duration per week (SDw) as the main parameters. To assess the DAS level, a validated Indonesian version of DASS was used [14]. The DASS was chosen because it is reliable and easy to administer, especially in conjunction with MCTQ or other relatively long questionnaires, therefore preventing respondents’ survey fatigue [11].

Parameter Calculation

Since there is a fundamental difference in the categorical interpretation of chronotype based on MSFsc between countries, geographical locations, and cultures, we decided to treat MSFsc as a linear scale, rather than categories (e.g. early, middle, or later phenotype). DASS were considered ordinal data as described [11]. MSFsc, the main parameter in determining the chronotype, is calculated by subtracting the mid-sleep time during free days from the sleep debt accumulated over a week, while SDw is the average of one week night’s sleep duration.

Qualitative Study

We conducted an in-depth interview to delineate whether chronotype shift preceded depression symptoms or vice versa. We only interviewed the subjects who fell into the extreme ends of both spectra, i.e. the later chronotype and high depression scores (n = 5). Interviews were performed either face-to-face or by telephone upon appointment. The questions were prepared beforehand but kept open-ended to facilitate data gathering concerning the phenomenon. The main questions were: 1) how long he/she has been having a late chronotype (“sleep late”); 2) whether the “sleeping late” preceded the feeling of being depressed; 3) was there any major event that influenced the sleeping pattern or induced depression; and 4) the difference between activities done before sleeping when they started to sleep late compared to when they slept “normally.”

Statistics

Quantitative data were entered into a master table, recording both the MCTQ and DASS scores, and the demographic characteristics. After removing incomplete entries (n = 8), the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). As appropriate, chi-square, Mann-Whitney U-test, and Spearman’s rank correlation tests were employed to calculate the statistical significance. Significance is set to be less than 0.05. Qualitative data such as the interview results were transcribed and analyzed qualitatively, by identifying common keywords and patterns among the respondents.

RESULTS

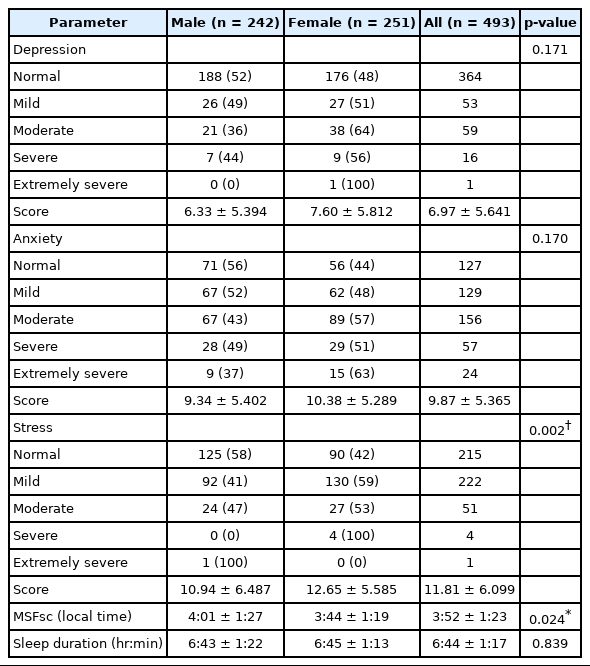

All the students (n = 501) agreed to participate and gave their consent to be included in the study. After the removal of incomplete questionnaires (n = 8), a representative group of 493 students (female = 251, 50.91%) was obtained and evaluated. The demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. After comparing the demography characteristics, DASS, and MCTQ parameters between sexes, we found differences in age, grades, as well as some habits such as coffee, smoke, and alcohol consumptions, which can be confounders in further analyses (Table 1). More importantly, we found a significant difference of MSFsc, the most important parameter of MCTQ, between males and females (Table 2). Based on these we further examined the relation between chronotype and DAS separately between males and females in subsequent analyses. Males had significantly later chronotypes compared to females (MSFsc 4:01 ± 1:27 vs. 3:44 ± 1:19, p = 0.024 by chi-square). In addition, a significant difference in stress level was also revealed (p = 0.002), where females perceived themselves as more stressed than males. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in sleep duration between sexes (6:43 ± 1:22 vs. 6:45 ± 1:13, p = 0.839).

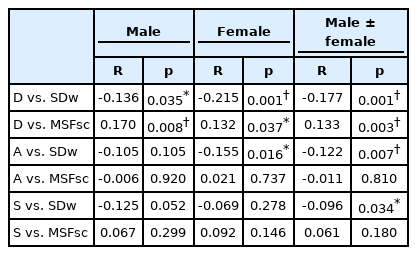

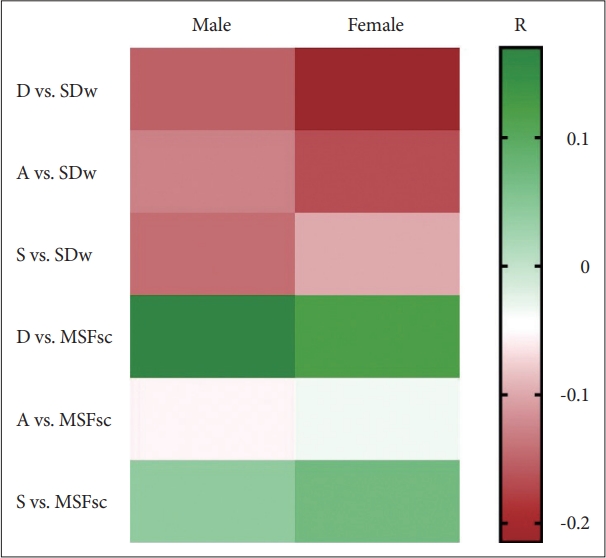

In general, our results showed that DAS negatively correlated with sleep duration but positively correlated with chronotype (Fig. 1). Statistical analyses showed that there is a small but significant correlation between depression score and MSFsc (Table 3), regardless of whether both sexes were analyzed together (R = 0.133, p = 0.003) or separately: in males, the R = 0.170, while for females R = 0.132 (p = 0.008 and 0.037, respectively). This demonstrates that subjects with higher depression scores exhibited a later chronotype. Interestingly, the depression score negatively correlated with the SDw. Both males (R = -0.136, p = 0.035) and females (R = -0.215, p = 0.001) exhibited the same inverse correlation between depression scale and SDw. Thus, the respondents with depressive symptoms not only sleep later, but they also sleep shorter. In addition, there is also a significant correlation between SDw and female anxiety score (R = -0.155, p = 0.016), and a weak correlation between overall group stress score with sleep duration (R = -0.096, p = 0.034).

The heatmap of R values (Spearman’s rank correlation) between each parameter in Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale and Munich Chronotype questionnaires. There is a negative correlation between DAS and sleep duration, and a positive correlation between DAS and MSFsc. Statistical calculations revealed significant correlations as described in Table 3. D, depression score; SDw, average sleep duration per week; A, anxiety score; S, stress score; MSFsc, sleep-deprivation corrected midsleep time at free days; DAS, depression, anxiety, and stress.

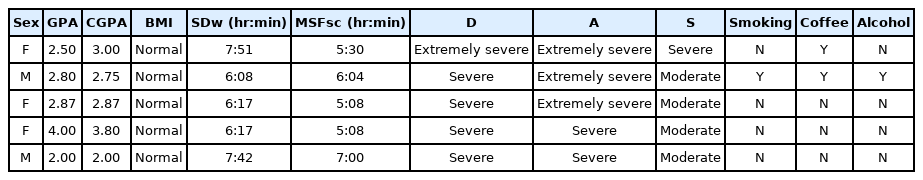

To follow up on these findings, we conducted qualitative research by tracing and interviewing the subjects with high depression scores (severe to extremely severe) with later chronotype (within the fifth quintiles of the MSFsc). We initially aimed to identify the arrow of causality (e.g. whether the late chronotype predated depression or vice versa), the factors that contribute to their lateness (e.g. what activities were being done before or during bedtime), the chronotype of their parents or siblings, and the possible cause of their depressive symptoms, for those who were willing to share. Surprisingly, all the interviewed subjects (Table 4, n = 5) were not aware that they scored high on the depression scale, and could not recall when was the first time they felt depressed. When asked about the potential causes of their depression, they picked some normative answers such as “I was being thoughtful (Indonesian: ‘pikir-pikir,’ a repetitive activity on thinking) about my grades” or “I am wondering about my future.” These findings rendered our initial aims to reveal the sequence of events and the causality arrow unreachable. Nevertheless, the rest of the interview acted as an explorative study about related properties of chronotype and depression. The most consistent item answered by the subjects is the activities that prevented them from sleeping early: all of them were engaged in different activities on their smartphones; social media, watching online videos, or games. All of them mentioned that the habit was formed during high school (approximately 3–4 years before this research), and it was currently almost impossible to go sleep without playing with their smartphones. While they all wanted to change their chronotype, they find it not urgent.

DISCUSSION

A Consistent Correlation Between Chronotype and Depressive Symptoms Across Latitudes as Shown by DASS

While there are many studies on mental health and chronotype, data from tropical and equatorial countries are lacking; to the best of our knowledge, so far, the comparable reports from the tropical areas came from limited sources such as Brazil and Taiwan, in which the chronotype and depressive symptoms were the main parameters [7,15-17]. Since the daylight duration is constant throughout the year in the equatorial area, the effect of seasonal sunshine deprivation on the mood may be negligible, thus rendering a very different pattern of the effects on mental health compared to the subtropical area. In the present research study, we replicated the findings of the previous studies, showing that even in the environment where the sun shines constantly, human chronotype varies, and more importantly, it correlates with mental health parameters, in particular with depressive symptoms. We observed a significant correlation between chronotypes (MSFsc and SDw) and depression score in both sexes, a phenomenon that has been well documented in studies on other subtropical areas [18-22]. It has been well established that seasonal affective disorders are related to the circadian cues from the sunlight, and many depression symptom outbreaks occur during winter, hence the term ‘winter blue’ [23]. The mood swing throughout the year may be a confounding factor in examining the depression symptoms, especially when using self-reported questionnaires such as DASS. Therefore, we thought that replicating such studies in an equatorial area may diminish the confounder and provide extended knowledge on depressive symptoms in relation to the other variables. Indeed, our current findings add to the available body of knowledge that, in the equatorial area where the seasonal daylight fluctuation is negligible, the correlation between chronotype and depression is preserved. It is notable that although there are strong correlations between DASS sections (D vs. A: R = 0.660, p < 0.001; D vs. S: R = 0.675, p < 0.001, A vs. S: R = 0.684, p < 0.001), the correlation with the chronotype is mostly existent in the depression section, which emphasized the validity of the currently used questionnaires in distinguishing subtypes of mental health symptoms.

There was a striking difference in the SDw between the present study and the previous studies. We found that our respondents had SDw of 6:44 ± 1:17 hours, lower than that reported in previous research studies from sub-tropical areas (multinational average around 7:48 hrs). However, on a closer examination, people from Asian countries have shorter SDw. Peltzer and Pengpid [24] reported a mean sleep duration of 6.59 hrs (range: 6.49–6.68 hrs) for Indonesia, comparable to Singapore (6.67 hrs), the Philippines (6.53 hrs), and South East Asia in general (6.82 hrs; range 6.78–6.87 hrs). In addition, Romadhon and Abdussalaam [25] reported that sleep duration in the Moslem community in Indonesia is around 5:58 to 6:15 hours with substantial variation across ages, thus adding a layer of complexity in determining a nationwide SDw. However, on top of this unique relatively short SDw, the effect of chronotype on depression symptoms is preserved.

Females Proneness to Stress

Across different cultures and countries, females have consistently been shown to be more likely to develop depression and anxiety disorders [26-28]. Our results also showed that female participants consistently scored higher in all parameters of DASSs as measured by DASS. The cause of this skewness across the literature has never been satisfactorily explained. Some explanation comes from socioeconomic factors [28] and the observation that females are more vulnerable to past adverse experiences [29]. Notably, our data showed that females relatively possess an earlier chronotype than males, despite having the same sleep duration. We would address this chronotype difference based on previous observations that females tend to sleep and wake up earlier than males [30,31] and the effect of testosterone in shaping late chronotype among males [32]. Thus, there seems to be an intrinsic uniqueness of self-perception of being depressed, anxious and stressed among females that cannot be explained by chronotype alone. Further research is necessary to confirm this. Some prospective research directions include providing different scoring criteria for women or tailoring specialized questionnaires based on gender.

Qualitative Research: Subclinical Depression?

Based on our findings, the respondents who scored high on the depression scale were unaware of being at the extreme severity scale during the qualitative analysis interview. Since DASS measures the symptoms of depression—instead of acting as a diagnostic tool as mentioned in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, there is a possibility that this could result in the inaccuracy of the self-reporting process. However, as discussed above, given the intrinsic validity of the DASS questionnaire between sections, it is unlikely that this unawareness could result from false-positive reporting. Instead, we would propose that subclinical depression may be imminent on these subjects, which is a predictor of future major depressive disorder [33,34]. In addition, the fact that these respondents are on the extreme late chronotype, as supported by previous research, places them at a high risk of developing depression [18-20,22].

Smartphones as a Source of Artificial Light and Potential Risk of Health-Related Problems in the Future

While our qualitative study is not sufficient to conclude that smartphone use is responsible for chronotype lateness and depression, it is well known that gadgets such as smartphones or tablets emit blue light that disrupts the circadian system putatively by interfering with the melatonin secretion [35]. Eventually, this lead to an increased incidence of a wide range of psychiatric and somatic disorders [36]. Sadly, gadget use is capable of inducing habituation and addictive behavior especially among youths and undergraduate students [37,38]. Furthermore, gadget use, as many other types of addiction, can provide a dopamine release in the brain reward system, thus providing a temporal release of stress, anxiety, or even subclinical depression as discussed above. In combination, this can lead to a vicious cycle of addiction-depression-coping that may need to be professionally intervened. This highlights the need for an initiative for controlling such behaviors and more effort to increase the student’s awareness of the imminence of gadget use. It has also been demonstrated that chronotype disturbance is related to a wide range of somatic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders [39], thus adding more reasons to include circadian rhythm management as a preventive measure against future pathologies.

Current Limitations and Future Research

Our present findings highlight the positive correlation between depression severity and chronotype, as well as a negative correlation between depression and sleep duration. While these three variables are not necessarily dependent, late-onset and short duration of sleep may reflect a low sleep quality. Thus, one of the immediate follow-up to this finding, and may be a future research topic, would be to evaluate whether depression indeed correlates with sleep quality. In addition, in the future, it is important to incorporate the circadian biomarker (e.g. plasma melatonin) examination in the subjects with extreme chronotype and perform experimental corrective studies such as assisted-chronotype restoration. While the present research study involved a relatively small population from a specific, homogenous group (college students) it may represent the societies in the equatorial area. However, further replication studies would be necessary to test the generalizability.

Conclusion

There is a correlation between chronotype and depression severity. Subjects with later chronotype tend to have higher depression score without being necessarily aware of it. The use of smartphones during or before bedtime may contribute to the shifting of the chronotype towards a later chronotype.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Supit A, Mamuaja P. Data curation: Gosal M. Formal analysis: Gosal M, Mamuaja P. Investigation: Supit A, Mamuaja P. Methodology: Supit A, Mamuaja P. Project administration: Paturusi A. Resources: Supit A. Software: Supit A. Supervision: Paturusi A. Validation: Gosal M, Supit A. Visualization: Supit A. Writing—original draft: Supit A, Kumaat S. Writing—review & editing: Supit A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Statement

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Head of Public Health Department and the Dean of the Faculty of Sport Science Manado State University for the permission to conduct the research on the campus site.