INTRODUCTION

In January 2020, a case of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in Wuhan, China. Since then, COVID-19 has been raging around the world and the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared it to be a pandemic [1]. Many countries had taken measures such as lockdowns (urban blockades) to minimize transmission of the virus.

Numerous studies have been conducted on how lockdown and lifestyle changes affect health aspects [2-4]. A web-based survey conducted during a lockdown in Italy found prevalences as follows: depression (25%), anxiety (23%), and insomnia (42%, 17% of whom had moderate or severe insomnia symptoms) [3]. A web-based survey conducted in Australia in April 2020 among 1491 adults reported decreased physical activity (49%), decreased sleep quality (41%), increased alcohol consumption (27%), and increased smoking (7%) since the pandemic occurred, which were exacerbated by depression, anxiety, and stress [4]. A study examining sleep changes during lockdowns in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria reported that although sleep duration increased overall, many suffered from poor sleep quality [2].

More than 2 years have passed since the COVID-19 outbreak, and perceptions of coronavirus and lifestyles have changed. The purpose of this study is to review how sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, commonly known as COVID-somnia, should be interpreted.

WHAT IS COVID-SOMNIA?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, sleep problems have been referred to as ‘COVID-somnia (or coronasomnia).’ This term refers to a wide range of sleep problems resulting from anxiety about infection of the virus, concerns about not being able to go to work, social isolation, and other factors brought on by the pandemic.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates of sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, involving a total of 54231 participants from 13 countries, reported a prevalence of insomnia symptoms of 35.7% [5]. In an international collaborative study, 17.4% of participants were identified with probable insomnia disorders while 36.7% had insomnia symptoms, with significantly lower rates in Eastern countries compared with Western countries (insomnia disorder: 8%–9% vs. 8%–31%; insomnia symptoms: 22%–25% vs. 28%–60%) [6].

In addition, patients infected with coronavirus were the most affected group, with a rate of 74.8% whilst health care workers and the general population had comparative rates of insomnia, with rates of 36.0% and 32.3%, respectively [6]. In South Korea, COVID-19 survivors had a 3.33-fold higher prevalence of insomnia disorders than that of a control group [7].

Thus, the prevalence of insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic is high, since approximately 20% of the general population is reported to have experienced insomnia symptoms before the COVID-19 outbreak [8,9]. It should be noted, however, that most of the studies for COVID-somnia were cross-sectional designs.

A few studies have examined changes in insomnia before and after the COVID-19 outbreak [10,11]. In Canada, the prevalence of insomnia increased from 25.4% to 32.2% from 2018 to 2020 (no statistical analysis was conducted) [10]. Of those classified as good sleepers in 2018, 32.6% had developed new insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. In Japan, the prevalence of insomnia symptoms in 2020 did not significantly increase, compared with those in 2018 and 2019 [11]. Individuals with sleep onset latency > 30 min represented 34% of the population in 2020 compared to 30% in 2018 and 29% in 2019; similarly, wake after sleep onset > 30 min was 13% compared to 11% and 10%, and sleep efficiency < 85% was 37% compared to 34% and 32%, respectively [11]. However, the number of individuals with sleep duration < 6 h was significantly decreased in 2020 (31%) compared to those in 2018 (38%) and in 2019 (34%) [11].

IS COVID-SOMNIA ONLY TEMPORARY?

In the above-mentioned study conducted in Canada, 32.6% of individuals had insomnia symptoms after the COVID-19 outbreak [10]. In comparison, the incidence of insomnia in the past 5 years before the COVID-19 outbreak was reported to be 13.9% in Canada [12]. In Japan, the prevalence of insomnia after a year was reported to be 9.9% before the outbreak [13]. In light of this, the prevalence of insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic is clearly higher. However, it is difficult to distinguish between individuals with conventional insomnia and temporary insomnia caused by COVID-induced infection anxiety.

If the anxiety is caused by fear of encountering the unknown, it may be a temporary symptom of insomnia that improves with time. For example, one study has examined changes in the incidence of insomnia after the Great East Japan Earthquake with the subsequent tunami, which was a huge earthquake with a moment magnitude of 9.0 on March 2011 [14]. It resulted in a major catastrophe that caused the death and disappearance of nearly 19000 residents. Compared to pre-earthquake levels in 2009, the prevalence of insomnia statistically increased nationwide immediately post-earthquake on July 2011 (11.7% vs. 21.2%), but significantly decreased to pre-earthquake levels on August 2012, compared to immediately after the earthquake (10.6% vs. 21.2%) [14].

In a study of changes in insomnia symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic, 55% of outpatients had insomnia symptoms in June 2020, but roughly half of them did not have insomnia symptoms 5 months later [15].

Hence, temporary insomnia due to encounters of the unknown may be an adaptive response for humans, similar to acute insomnia. Therefore, study designs that define COVID-somnia as synonymous with conventional insomnia during COVID-19 are limited. To examine the association between COVID-19 and sleep problems, it is necessary to consider the impact of pandemic-specific phenomena, such as anxiety about infection, on sleep problems.

MEASUREMENTS OF ANXIETY ABOUT INFECTION

Some scales have been developed after the COVID-19 outbreak. The two scales most frequently used are the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) [16] and the COVID Stress Scale (CSS) [17]. The SAVE-9 was constructed using nine items with two domains; 1) anxiety about viral epidemics and 2) work-related stress associated with viral epidemics [16]. The CSS was constructed using 36 items with five domains; 1) danger and contamination fears, 2) fears about economic consequences, 3) xenophobia, 4) compulsive checking and reassurance seeking, and 5) traumatic stress symptoms [17].

Both scales have high reliability and validity and have been translated into many languages. SAVE-9 has a small number of items and measures anxiety about infection, thus it can be used in the event of a new viral pandemic. The CSS measures various aspects of anxiety about infection, but it has a large number of items and is specific to COVID-19–related anxiety.

Two studies have examined the relationship between anxiety about infection, measured by SAVE-9 or SAVE-6, and sleep problems [18,19]. The results of these two studies are inconsistent. For health workers, infection anxiety was associated with worse sleep problems and the subsequent mental health issues [18]. However, infection anxiety did not affect sleep problems, loneliness, and school refusal in adolescents [19]. Although both studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is noteworthy that the results showed different effects of infection anxiety on sleep problems in a given population.

IS COVID-SOMNIA FACT OR FICTION?

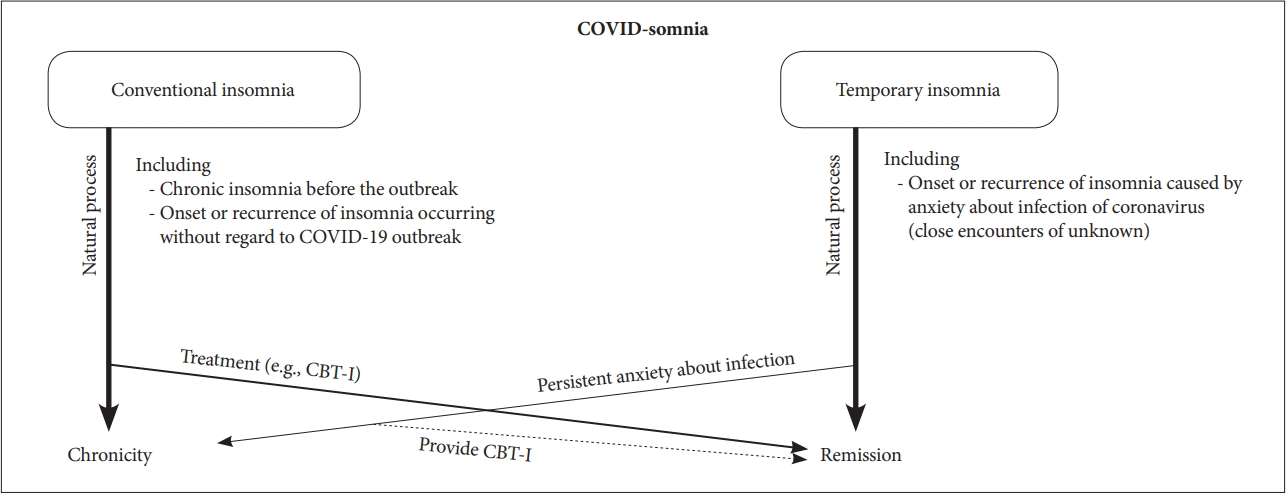

COVID-somnia is a mixed concept, consisting of conventional chronic insomnia and temporary insomnia (Fig. 1). It is possible that most cases are illusory and that only a few people are actually going to suffer from an insomnia disorder, although the prevalence of insomnia appears to have increased after the outbreak. However, it is also true that they complain of temporary insomnia symptoms. Therefore, it is likely to decrease insomnia with accurate knowledge of the coronavirus and effective infection control strategies such as vaccination, mask wearing, and sanitizing their hands for temporary insomnia. Habituation to the pandemic circunstances over time may also be related to a decrease in insomnia symptoms. Since unprecedented pandemics have time to provide evidence of the virus and countermeasures, it is necessary to disseminate sleep hygiene education that do not cause mental and physical illness.

Individuals with high anxiety about infection, e.g., patients with anxiety-related disorders [20], may continue to have persistent insomnia symptoms or develop an insomnia disorder. For example, negative effects of COVID-19–related anxiety are more strongly linked to contamination and responsibility for harmful symptoms for individuals with obssessive compulsive disorder symptoms [21].

EVIDENCE-BASED APPROACH FOR CONVENTIONAL INSOMNIA

Currently, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is effective for insomnia with/without psychiatric and physical illness comorbidities [22-24]. Meta-analyses show that CBT-I is an effective treatment for reducing, not only the severity of insomnia, but also important disease-related symptoms (e.g., depressive mood in major depression) of comorbid insomnia [23,24]. Therefore, CBT-I is likely to be effective for persistent insomnia due to infection anxiety. Of course, it will be important to implement CBT-I for conventional insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic.

CBT-I is available in face-to-face and self-help forms, both of which are highly effective [25]. Especially in the COVID-19 pandemic, self-help CBT-I, in digital form, booklet, or e-mail delivered, can be administered without face-to-face contact and this may be effective. For example, digital CBT-I has been shown to improve insomnia severity and work productivity in workers with insomnia [26,27], and e-mail delivered CBT-I has been shown to improve insomnia and mental health in college students [28-31]. Therefore, not only face-to-face CBT-I but also self-help CBT-I should be actively utilized for chronic insomnia during the pandemic.

Interestingly, individuals with insomnia who previously received digital CBT-I before the COVID-19 outbreak reported less insomnia severity, less COVID-related cognitive intrusions, less depression, and better global health than those who received sleep education [32]. Moreover, the odds ratio for recurrent insomnia was 51% lower in the digital CBT-I compared with control condition, and odds for onset of moderate to severe depression was 57% lower in the digital CBT-I during COVID-19 [32]. Therefore, it would be better to actively provide CBT-I to insomniacs in order to build up their stress tolerance for encountering the unknown in the future.

CONCLUSION

Future study is needed to determine the demographic and personality characteristics of individuals with persistent anxiety about infection. It is also necessary to examine whether the development and provision of interventions specific to COVID-somnia with anxiety about infection are effective in the future. In this review, we have focused on insomnia, which has the highest number of study reports among COVID-somnia. For sleep disorders other than insomnia, it will be necessary to distinguish between temporary and conventional symptoms and examine changes over time.