AbstractBackground and Objective The aim of this study is to explore the usefulness of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic-3 items (SAVE-3) scale as a tool for assessing work-related stress in healthcare workers.

Methods There were 389 participants and all remained anonymous. The SAVE-9, the Patient Health Questionnaire-4, the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS-MP), the perceived stress scale (PSS), and single item insomnia measure were used. After checking whether the SAVE-3 scale is clustered into a sole factor from SAVE-9 scale based on principal component analysis with promax rotation, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was done on the 3 items of the SAVE-3 to examine the factorial validity for a unidimensional structure.

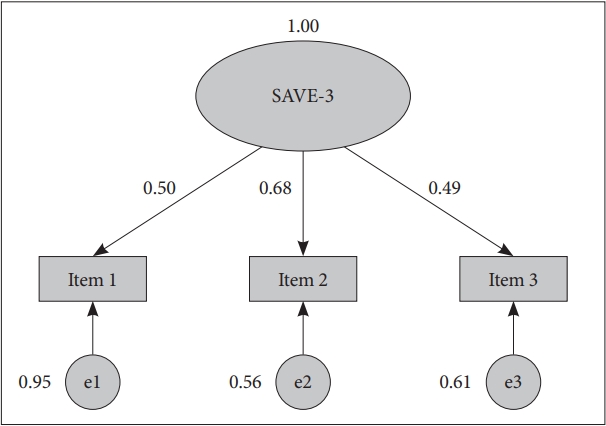

Results The SAVE-3 was clustered with factor loadings from 0.664–0.752, and a CFA revealed that 3 items of the SAVE-3 cohered together into a unidimensional construct with fit for all of indices (comparative fit index = 1.00; Tucker Lewis index = 1.031; standardized root-mean-square residual = 0.001; root-mean-square-error of approximation = 0.00). The SAVE-3 scale showed acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.56 and McDonald’s ω = 0.57) in this sample. A high SAVE-3 score correlated significantly with younger age (r = -0.12, p = 0.02), a high PSS score (r = 0.24, p < 0.001), a high total score for the MBI-HSS-MP (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and all of its subscales (emotional exhaustion, r = 0.40, p < 0.001; personal accomplishment, r = -0.14, p < 0.005; depersonalization, r = 0.39, p < 0.001), and poor sleep quality (r = 0.15, p < 0.001).

INTRODUCTIONDuring 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak spread rapidly to countries worldwide. During the outbreak, healthcare workers have suffered high levels of psychological distress as they care for patients, placing themselves at high risk of exposure to this potentially fatal infectious disease [1-3]. Healthcare workers face unprecedented and unfamiliar clinical roles, increased workloads, social discrimination, and a feeling of being scrutinised by the public, government, and media [3,4]. Contrary to the “normal” disasters, contagious epidemics have an adverse effect not only on the victims but also on caregivers. Therefore, it is important to assess levels of psychological distress and work-related stress in this population.

Previous studies [2,3,5-7] demonstrate that healthcare workers show a consistent pattern of psychological reactions to infectious disease outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome, influenza A/H1N1 and Middle East respiratory syndrome. Healthcare workers working during such outbreaks suffer from a shortage of supplies, personnel and resources. In addition, they suffer from work overload, irregular work patterns, fear of contagion for themselves, their families and colleagues, working with constantly changing protocols and discomfort caused by having to wear personal protective equipment. Work-related stress can have many negative psychological effects, including burnout, fatigue, anxiety, depression, acute stress reactions and post-traumatic stress disorder [1-3].

The COVID-19 pandemic has lasted for more than 1 year, during which many studies reported the psychological consequences experienced by healthcare workers in different countries. Lu et al. [8] explored the immediate psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers in China. They found that 29.8%, 13.5% and 24.1% of subjects showed symptoms of stress, depression and anxiety, respectively. Another study shows that 3.8% of healthcare workers reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress as early as 1 month after the COVID-19 outbreak [9]. Other studies report a high prevalence of burnout among healthcare professionals [9,10]. Healthcare workers suffer from emotional exhaustion or work-related stress due to the fear of contagion while taking caring of patients, lack of personal protective equipment [11], anxiety about the safety of themselves and their family members or friends [12]. Therefore, it is essential to identify and treat work-related stress to protect the mental health and wellbeing of healthcare workers during the pandemic. However, the rating scale which can be used to measure work-related stress of healthcare workers specifically in response to the viral epidemic was not developed yet. In numerous studies, mental health of healthcare workers was assessed using well-known rating scales such as Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [13], Copenhagen Burnout Inventory [14], or perceived stress scale (PSS) [15], which were already well validated among healthcare workers. However, these scales are not specific to the viral epidemic but to the general situation. In pandemic era, a briefly measureable, viral epidemic-specific, and healthcare workers-specific rating scale is so useful to assess their work-related stress in response to the viral epidemic.

Recently, we developed the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic-9 items (SAVE-9) scale, which is designed to assess workrelated stress and anxiety in healthcare workers specifically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [16], and it was validated in Russian [17], Italian [18], Turkish [19], Germany [20], and Japanese [21]. This scale was originally reported to be clustered into two subcategories [16]; Factor I examines the anxiety response to the viral epidemic (SAVE-6) and Factor II examines work-related stress associated with the viral epidemic (SAVE-3). The former SAVE-6 was already validated for the utility of assessing viral anxiety among general population [22-24]. In this study, we aimed to examine the unidimensional construct validity of the 3-item work-related stress associated with the viral epidemic subscale of the SAVE-9, namely SAVE-3, and we wanted to explore the utility of SAVE-3 to assess work-related stress of healthcare workers specifically in response to the viral epidemic in this pandemic era.

METHODSParticipants and ProceduresThe study was conducted via an anonymous online survey at the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Participants were recruited from the hospital via an advertisement posted on the intranet. The advertisement explained the study’s objective, enrolment procedure and the reward for participants. From the 28th of January, 2021, to the 29th of January, 2021, 389 workers were enrolled and responded voluntarily to the survey. In return they received a coupon valued at about $3. The study protocol was approved and obtaining the written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board (2021-0124) of the Asan Medical Center.

Symptom AssessmentStress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic-3 items (SAVE-3)The SAVE-3 scale is a subcategory of the original SAVE-9 scale developed by Chung et al. [16] at ASAN Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine (https://www.saveviralepidemic.net). The original SAVE-9 scale was designed to assess work-related stress and anxiety in healthcare workers in response to the viral epidemic [16]. It is clustered into two factors. Factor I contains six items to assess anxiety about the viral epidemic (SAVE-6) [22] and Factor II contains three items to assess work-related stress associated with the viral epidemic (SAVE-3). Respondents answer each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The total score for the SAVE-3 scale ranges from 0–12; higher scores reflect a more severe degree of work-related stress.

Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4)The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) was developed to assess two of the most prevalent psychiatric symptoms among the general population [25]. It is an ultra-brief scale that combines the PHQ-2 [26] and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) [27], which assess core symptoms of depression and anxiety. Each of the four items in the PHQ-4 are rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). A score of 3 or greater on the Depression or Anxiety subscales represents a cut-off point for potential cases of depression or anxiety. Such cases are assessed further using the PHQ-9 or GAD-7 as needed.

Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS-MP)The MBI is used widely to assess burnout. It has three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and personal accomplishment (PA) [28]. In this study, the medical personnel version of the MBI was used. The 22 items are rated on a 7-point scale from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). Higher total scores indicate higher degrees of burnout. The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS-MP) scale can be clustered into three subscales: a nine-item EE scale, a five-item DP scale and an eight-item PA scale.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)The PSS is a self-reporting scale designed to measure the perceived severity of stress [29]. It comprises 10 items (revised down from the original 14 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Six items are negative statements and four items are positive statements. Total scores range from 0–40; a higher score means a higher degree of subjective stress. This study used the Korean version of the PSS-10 [30].

Statistical AnalysisFirst, we tested the normality assumption of the SAVE-9 scale using skewness and kurtosis for an acceptable limit of range ± 2 [31], checked sampling adequacy and data suitability using Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity, and conducted scree test and principal component analysis (PCA) with promax rotation to explore the factors of the SAVE-9 scale. Second, after checking whether the SAVE-3 scale is clustered into a sole factor, we conducted statistical analysis to explore the structure validity of the SAVE-3 scale. The normality assumption was checked using skewness and kurtosis for an acceptable limit of range ± 2 [31]. After examining the KMO measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity, a bootstrap (2000 samples) maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was done on the 3 items of the SAVE-3 to examine the factorial validity for a unidimensional structure. Multigroup CFAs were run to explore whether the SAVE-3 is measuring work-related stress in response to the viral epidemic in the similar way respect to sex (male vs. female), job (nursing professionals vs. others), experience of taking care of infected patients (yes vs. no), and feeling depressed or anxious (using the PHQ-4; yes vs. no). Satisfactory model fit was defined by a standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) value ≤ 0.05, root-mean-square-error of approximation (RMSEA) value ≤ 0.10, and comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis index (TLI) values ≥ 0.90 [32,33]. Last, the reliability and internal consistency of the factor was examined using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficient to verify dimensionality of the SAVE-3 scale. The independent t-test were done to examine to examine differences in the SAVE-3 score with respect to sex, marital status, experience of taking care of infected patients (yes vs. no), being quarantined (yes vs. no) and feeling depressed or anxious (using the PHQ-4; yes vs. no). And also we used Pearson’s correlation analysis to examine the correlation between the total SAVE-3 score and age, years of employment, number of COVID-19 nasal swab tests and the scores of rating scales including PSS, MBI-HSS-MP, and insomnia single item. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and AMOS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTSThe 389 healthcare workers included 55 medical doctors, 247 nursing professionals and 87 “other” healthcare workers (Table 1). Of these, 335 (86.1%) were female and nearly one third (28.9%) were shift-workers. The mean age was 35.3 ± 8.0 years and the mean number of years of employment was 10.6 ± 8.3. Among the respondents, 120 (30.8%) and 70 (18.0%) were rated as having depression (depression scale score in the PHQ-4 ≥ 3) or generalised anxiety (anxiety scale score in the PHQ-4 ≥ 3). Also, 74 (19.0%) experienced taking care of patients who were infected and 36 (9.3%) experienced being quarantined. Just one experienced being infected themselves. The mean number of COVID-19 nasal swab tests per subject was 3.2 ± 2.7.

Confirming the Factor Structure of the SAVE-9 ScaleIn this study we explored the factor structure of the SAVE-9 scale to confirm whether it can be clustered into two factors in this sample. We checked the normality of the items of SAVE-9 scale, and we observed that the skewness of the items were -0.999–0.407, and the kurtosis of items were -0.719–1.483 (Table 2). The SAVE-9 scale data was suitable and sampling was adequate to perform the PCA (KMO = 0.865; Bartlett’s Sphericity, p < 0.01). The scree test showed that the SAVE-9 scale can be clustered into two factors with eigenvalues of 3.538 for Factor I and 1.048 for Factor II. PCA analysis with promax rotation revealed that the SAVE-9 was clustered into Factor I (item 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 8, namely SAVE-6) with factor loadings from 0.564–0.780, and Factor II (item 6, 7 and 9, namely SAVE-3) with factor loadings from 0.664–0.752. The SAVE-9 scale showed good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.80 and McDonald’s ω = 0.81) in this sample.

Factor Structure of the SAVE-3 Scale, Reliability of the Scores, and Evidence Based on Relations to Other VariablesThe normality of items in the SAVE-3 scale was checked and the distribution of each 3 items were within the normal limit based on skewness and kurtosis ranged within ± 2 (Table 3). The KMO measure (0.610) and Bartlett’s Sphericity (p < 0.001) showed that the samples seem compatible for the factor analysis. A CFA revealed that 3 items of the SAVE-3 cohered together into a unidimensional construct with fit (Fig. 1) for all of indices (CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.031; SRMR = 0.001; RMSEA = 0.00). Multigroup CFAs were run to examine if the construct of the SAVE-3 was being measured in same way across gender (men vs. women, CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.029; SRMR = 0.014; RMSEA = 0.00), job (nursing professionals vs. others, CFI = 0.988; TLI = 0.988; SRMR = 0.052; RMSEA = 0.038), experience of taking care of infected patients (yes vs. no, CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.042; SRMR = 0.054; RMSEA = 0.00), feeling depressed (depression scale of the PHQ-4 ≥ 3; yes vs. no, CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.131; SRMR = 0.026; RMSEA = 0.00), or feeling anxious (anxiety scale using the PHQ-4 the PHQ-4 ≥ 3; yes vs. no, CFI = 0.996; TLI = 0.996; SRMR = 0.074; RMSEA = 0.020).

The SAVE-3 scale showed acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.56 and McDonald’s ω = 0.57) in this sample. A high SAVE-3 score correlated significantly with younger age (r = -0.12, p = 0.02), a high PSS score (r = 0.24, p < 0.001), a high total score for the MBI-HSS-MP (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and all of its subscales (EE, r = 0.40, p < 0.001; PA, r = -0.14, p < 0.005; DP, r = 0.39, p < 0.001), and poor sleep quality (r = 0.15, p < 0.001). The SAVE-3 scores were also significantly higher in workers rated as having anxiety (anxiety scale score PHQ-4 ≥ 3, [t(387) = 6.58, p < 0.001]) or depression (depression scales score PHQ-4 ≥ 3, [t(387) = 6.45, p < .001]), and in those who reported that they needed immediate psychological help with their psychiatric symptoms [t(387) = 2.86, p < 0.001]. However, there was no significant difference in the SAVE-3 scores with respect to experience of caring for infected patients [t(387) = 1.33, p = 0.19], being quarantined [t(387) = 1.38, p = 0.17], past psychiatric history [t(384) = 0.87, p = 0.53], sex [t(387) = 0.35, p = 0.73], and nursing professionals versus other [t(384) = 1.43, p = 0.16].

DISCUSSIONWe aimed to examine the factorial validity of the SAVE-3 scale and the utility to assess work-related stress of healthcare workers specifically in response to the viral epidemic in this pandemic era. The results support use of the single-factor SAVE-3 model for this purpose as the scale demonstrated an excellent fit for all indices, and measurement invariance with respect to sex, job, experience of taking care of infected patients, depression, or anxiety. In addition, the SAVE-3 scale demonstrated satisfactory reliability for this cohort. The SAVE-3 showed the good convergent validity with the validated burnout rating scale (MBI-HSS-MP) and rating scales about the perceived stress, depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Our results support the use of SAVE-3 as a tool for assessing work-related stress in healthcare workers in COVID-19 pandemic.

Originally, we developed the SAVE-9 scale to assess stress and anxiety in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic [16]. In that study, the SAVE-9 scale was clustered into two factors. Factor I comprised six items and examined anxiety about the viral epidemic (SAVE-6), and Factor II comprised three items and examined work-related stress associated with the pandemic (Factor II was named SAVE-3). In this study, we hypothesised that the simpler SAVE-3 scale may be a useful tool for measuring work-related stress in healthcare workers during the viral epidemic. In the present study, PCA showed that this clustering pattern was replicated in this sample in accordance with the previous studies [16,18,21], though one previous study showed different clustering [17]. In Russian healthcare workers sample, items 2, 3, 4, and 8 were included in the Factor I and items 1, 5, 6, 7, and 9 were included in the Factor II. In Russian sample, item 1 and 5 were clustered into work-related stress (Factor II) rather than anxiety response about the viral epidemic (Factor I), and it might come from the cultural difference. However, items 6, 7, and 9 were clustered into Factor II among all previous studies, and we considered that the SAVE-3 can be used solely from the PCA result among healthcare workers sample in the present study.

The CFA of the SAVE-3 in this study showed good fit for unidimensional model, but the internal consistency was relatively low (McDonald’s ω = 0.57, Cronbach’s α = 0.56). Generally, Cronbach’s α = 0.6–0.7 is considered to be an acceptable level of reliability. We accepted this value and did not try to increase it by excluding items since the main objective of the study is to explore the applicability and validity of the SAVE-3 scale when used alone. The factor loadings of 3 items were 0.475, 0.599, and 0.712, though usually over 0.6 of factor loading value was considered to be acceptable [34]. This low factor loading of item 1 of the SAVE-3 (Do you feel skeptical about your job after going through this experience?) might come from the high proportion of responses (47.1%) of “never or rarely.” This survey was conducted from the 28th of January, 2021, to the 29th of January, 2021, and 1 years already passed after the first outbreak in South Korea. We can speculate that healthcare workers might adapt the long periods of pandemic and they may think to keep continuing working in the hospital in this pandemic. However, another speculation is that healthcare workers can think to keep their working regardless of viral outbreak. In our previous study conducted on April 20–30, 2020 [16], we also observed the high proportion of responses (64.5%) of “never or rarely” to the same item. These results may come from cultural differences between South Korea and other countries. Anyway, this low factor loading value might be considered when this scale is applied in clinical setting.

To examine convergent validity, we applied the MBI-HSS-MP and PSS alongside the SAVE-3 scale. The SAVE-3 scale score correlated significantly with the total scores for the MBI-HSSMP (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and all its subscales (EE, r = 0.40, p < 0.001; PA, r = -0.14, p < 0.005; DP, r = 0.39, p < 0.001). The MBI-HSS-MP scale is a widely used rating scale for measuring burnout of healthcare workers [28]. In hospitals, particularly during this pandemic, burnout of healthcare workers due to heavy workloads results in very serious psychological distress. In addition, a high SAVE-3 score correlated significantly with a high PSS score (r = 0.24, p < 0.001). The PSS is the most widely used scale for measuring the degree to which situations are regarded as stressful. During the pandemic era, healthcare workers perceive this unusual risk as stressful. In addition, the SAVE-3 scale score was observed to be higher significantly in workers rated as having anxiety or depression. The SAVE-3 can be helpful to explore anxiety or depression of healthcare workers. The SAVE-3 score was also correlated with poor sleep quality. The SAVE-3 is useful for exploring the three most popular psychiatric symptoms of healthcare workers: anxiety, depression, and insomnia. We considered that it is reasonable to use the SAVE-3 scale alone during this pandemic era.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted via an anonymous online survey. The pandemic makes it difficult to conduct face-to-face interviews to collect information. Second, most participants were nursing professionals (63.5%); therefore, the results may not adequately reflect stress experienced by other healthcare workers. Third, the results do not accurately reflect stress experienced by infected healthcare workers since only one participant was infected. Fourth, the single item question for sleep quality was not validated formally. More reliable scale needs to be applied. In further study, it needs to be considered. Fifth, we did not perform a test-retest correlation.

In conclusion, we found that the SAVE-3 scale is a brief, reliable and valid scale that can be used to measure work-related stress in healthcare workers during the viral pandemic. There are numerous dimensions to work-related stress, but these need to be fine-tuned and applied to a “viral epidemic-specific” rating scale that can measure work-related stress accurately. We hope that the SAVE-3 will be a simple and useful tool for assessing the status of frontline healthcare workers.

NOTESAvailability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Chung S, Suh S. Data curation: Chung S, Son HS, Kim K, Cho IK, Lee J. Formal analysis: Son HS, Chung S, Ahn MH. Funding acquisition: Suh S. Investigation: Suh S. Methodology: Chung S, Ahn MH, Suh S. Writing—original draft: Chung S, Son HS. Writing—review & editing: Ahn MH, Kim K, Cho IK, Lee J, Suh S.

REFERENCES1. Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ 2003;168:1245-51.

2. Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ 2004;170:793-8.

3. Maunder R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: lessons learned. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2004;359:1117-25.

4. Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:1055-7.

5. Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:127-33.

6. Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho AR, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry 2018;87:123-7.

7. Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, Barnard AG, Qushmaq IA. Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clin Med Res 2016;14:7-14.

8. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:112936.

9. Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, Ni X, Deng X, Jia Y, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019. Clin Psychol Psychother 2020;27:384-95.

10. Marôco J, Marôco AL, Leite E, Bastos C, Vazão MJ, Campos J. Burnout in Portuguese healthcare professionals: an analysis at the national level. Acta Med Port 2016;29:24-30.

11. Gray M, Monti K, Katz C, Klipstein K, Lim S. A “Mental Health PPE” model of proactive mental health support for frontline health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2021;299:113878.

12. Zhang M, Murphy B, Cabanilla A, Yidi C. Physical relaxation for occupational stress in healthcare workers: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Occup Health 2021;63:e12243.

13. Cena L, Rota M, Calza S, Massardi B, Trainini A, Stefana A. Mental health states experienced by perinatal healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:6542.

14. Fteropoulli T, Kalavana TV, Yiallourou A, Karaiskakis M, Koliou Mazeri M, Vryonides S, et al. Beyond the physical risk: psychosocial impact and coping in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Nurs 2021 Jul 6;[Epub]https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15938.

15. Karabulut N, Gürçayır D, Yaman Aktaş Y, Kara A, Kızıloğlu B, Arslan B, et al. The effect of perceived stress on anxiety and sleep quality among healthcare professionals in intensive care units during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychol Health Med 2021;26:119-30.

16. Chung S, Kim HJ, Ahn MH, Yeo S, Lee J, Kim K, et al. Development of the stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) scale for assessing work-related stress and anxiety in healthcare workers in response to viral epidemics. J Korean Med Sci 2021;36:e319.

17. Mosolova E, Chung S, Sosin D, Mosolov S. Stress and anxiety among healthcare workers associated with COVID-19 pandemic in Russia. Psychiatr Danub 2020;32:549-56.

18. Tavormina G, Tavormina MGM, Franza F, Aldi G, Amici P, Amorosi M, et al. A new rating scale (SAVE-9) to demonstrate the stress and anxiety in the healthcare workers during the COVID-19 viral epidemic. Psychiatr Danub 2020;32:5-9.

19. Uzun N, Akça ÖF, Bilgiç A, Chung S. The validity and reliability of the stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-9 items scale in Turkish health care professionals. J Community Psychol 2021 Aug 16;[Epub]https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22680.

20. König J, Chung S, Ertl V, Doering BK, Comtesse H, Unterhitzenberger J, et al. The German translation of the stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) scale: results from healthcare workers during the second wave of COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:9377.

21. Okajima I, Chung S, Suh S. Validation of the Japanese version of stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) and relationship among stress, insomnia, anxiety, and depression in healthcare workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. Sleep Med 2021;84:397-402.

22. Chung S, Ahn MH, Lee S, Kang S, Suh S, Shin YW. The stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-6 items (SAVE-6) scale: a new instrument for assessing the anxiety response of general population to the viral epidemic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 2021;12:669606.

23. Hong Y, Yoo S, Mreydem HW, Abou Ali BT, Saleh NO, Hammoudi SF, et al. Factorial validity of the Arabic version of the stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-6 items (SAVE-6) scale among the general population in Lebanon. J Korean Med Sci 2021;36:e168.

24. Lee S, Lee J, Yoo S, Suh S, Chung S, Lee SA. The psychometric properties of the stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-6 items: a test in the U.S. general population. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:746244.

25. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009;50:613-21.

26. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284-92.

27. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:317-25.

28. Maslach C, Jackson DE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach burnout inventory. Menlo Park: Mind Garden 1986.

29. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385-96.

30. Lee J, Shin C, Ko YH, Lim J, Joe SH, Kim S, et al. The reliability and validity studies of the Korean version of the perceived stress scale. Korean J Psychosomatic Med 2012;20:127-34.

31. Gravetter FJ, Wallnau LB. Essentials of statistics for the behavioral sciences. 8th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth 2014.

32. Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press 2006.

33. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates 2001.

34. Awag Z. Structural equation modeling using AMOS graphic. Shah Alam: UiTM Press 2012.

Fig. 1.A unidimensional construct of the SAVE-3 scale. SAVE-3, Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic-3 items.

Table 1.Demographic characteristics of the study participants (n = 389) Table 2.Frequency of participant answers to each item of the SAVE-9 scale (n = 389) Table 3.Frequency of participant answers to each item of the SAVE-3 scale (n = 389) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||